Updated Dec. 23 – Re: Molhem’s compensation

Updated Dec. 24 – Initial responses

Updated Jan. 8 – New details raise still more questions

Updated Mar. 17 – Some answers

Reuters, a big-leagues news service owned by a $13 billion multinational corporation, is ducking critical questions about the death of a teenage war photographer who’d been selling pictures to the agency.

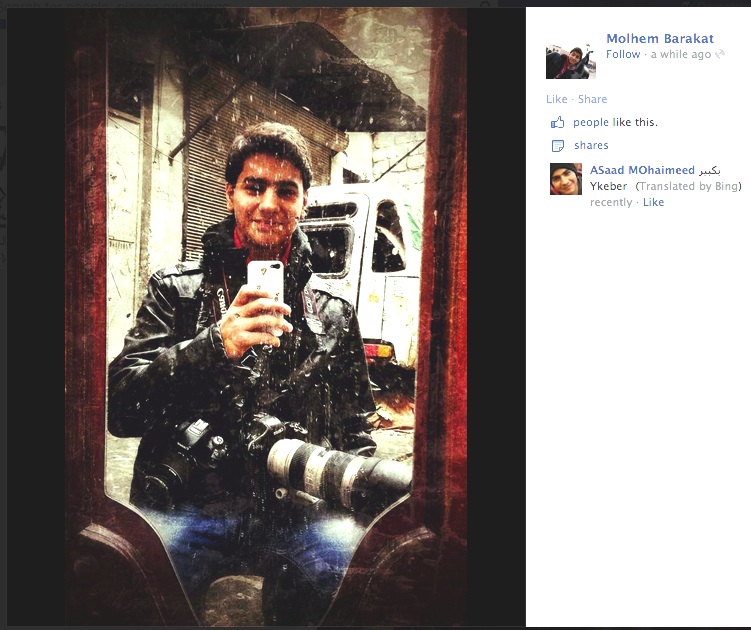

Molhem Barakat was reportedly killed on December 20 while covering a battle over a hospital in Aleppo, Syria.

Reuters distributed his pictures around the world and some appeared on the websites of such prestigious publications as the New Yorker magazine and The New York Times.

Reports of Molhem’s age ranged between 17 and 19. Strangely, Reuters’ own story on his death omits this standard biographical detail.

Some who followed the story of Molhem’s death memorialized Molhem and his work, while others, myself included, raised questions about how it was that an inexperienced teenager came to be working for a major news organization in a war zone.

BBC journalist Stuart Hughes, who I know is personally concerned with the working conditions of journalists in war zones, sent some questions to Reuters regarding their procedures for verifying the ages of freelancers in hostile environments, and other essential backround, such as what training Molhem might received.

Reuters replied with a blunt and frankly nonsensical refusal to discuss the situation:

We are deeply saddened by the death of Molhem Barakat, who sold photos to Reuters on a freelance basis. To best protect the many journalists on the ground in a dangerous and volatile war zone, we think it is inappropriate to comment any further at this time

Of course, just because Reuters calls Molhem a freelancer does not mean that he was a freelancer under the law. And whether he was a freelancer or not, legally speaking, the agency had a responsibility to ensure that he was prepared for the work it was actively encouraging him to pursue.

For what it’s worth, Molhem’s Facebook page shows that he considered himself a Reuters employee:

Before I saw the agency’s wholly inadequate response to Stuart’s inquiries, I had prepared my own list of questions for Reuters.

Here are those questions.

But first, I know first-hand that Reuters may not be alone in its labor practices. The current economics of the news business made a story like this one all but inevitable. That Molhem had not even reached age 20 makes what happened all the more saddening, and infuriating.

I know too that wars are messy, and if Molhem hadn’t been taking pictures, he may well have taken up arms. The Reuters team in Syria might have thought they were doing him a favor — and in some ways, I’m sure that they were.

That doesn’t mean the company gets to blow off questions about the circumstances leading up to this young man’s death.

- Why did Reuters not mention Molhem’s age in its report on his death? If the agency did not know his true age, why not?

- Who besides the named editor reviewed the report on his death before publication? Was it reviewed by lawyers? [What about the statement published in response to the BBC’s questions?]

- What were the nature of injuries that led to Molhem’s death? How did Reuters learn about what had happened to him?

-

Is Reuters in contact with his next of kin? Has the company made any <span=”payment”>offer of assistance for instance to defray the funerary expenses?

-

Did Molhem sell pictures to any other news organizations? What percentage of his income did Reuters provide?

-

Did he have any contract with Reuters? What did it stipulate?

-

How often did he submit pictures? How many of those pictures were accepted?

-

Was he provided with any equipment from Reuters? What type? Did Reuters offer him a bulletproof vest, helmet or eye protection? A satellite phone?

-

Was he provided with safety training? Was he provided with any training whatsoever?

-

Was he insured? Did Reuters offer any subsidy for this?

-

Who were his points of contact at Reuters?

-

Did they ever suggest he cover certain stories or travel to certain locations?

-

Did they suggest how he might improve his work or make it more salable? Did they for instance ever suggest that he get closer to his subjects?

-

Did they ever warn him against covering a certain story out of concern for his safety? If so, what circumstances triggered those warnings?

-

Did he ever cover stories that under the same or similar circumstances would have been deemed too dangerous for a full-time Reuters employee?

-

Did they ever hold out the possibility of advancement or full-time employment within Reuters?

-

Did they ever hold out the possibility of offering help with employment, education or amnesty abroad?

-

Why was he not hired as a full-time employee?

-

If he might have been deemed too inexperienced or unqualified to gain a staff job, why was he deemed fit to submit work from an immensely challenging, complex and dangerous environment?

Molhem was paid as little as $100 for uploading a daily set of 10 or more photos to Reuters, according to a freelance photographer who met Molhem earlier this year in Aleppo and stayed in touch with him.

The photographer, Stanislav Krupar, says Molhem told him this at a Free Syrian Army base that hosted members of the news media. Molhem told Krupar that Reuters also paid him a bonus of $50 or $100 when one of his photos was selected as a Picture of the Day on the popular New York Times Lens Blog.

I’ve emailed Reuters global head of communications Barb Burg to comment on, confirm or disconfirm, this information.

Krupar says Molhem started out with his own cheap camera, but eventually received better hand-me-down equipment from Reuters.

“I am absolutely sure that the photo gear he had was provided by Reuters,” the Prague-based photojournalist writes.

He says Reuters gave Molhem at least one camera body and two lenses, including the gear shown covered in blood in this widely distributed picture.

However, Krupar does not believe that Molhem received safety gear from the agency:

I have not seen [Molhem with] any ballistic protection – no vest, no helmet. He had nothing.

Kruapr goes on:

Personaly Molhem was very carefull not to say too much about his work and contract. He pretended to be 19 years old, though [I] was sure that he must be younger. … [W]e had a feeling that he has a lot of to hide…

But as I remember he told me that he is paid 100 dollars for load of 10 uploaded photos a day. Plus some 50 or 100 dollars as a benefit when his work is awarded as “Picture of a Day” on [the] Lens Blog [of the] New York Times.

Krupar also sent me the following photo showing Molhem filing pictures from an FSA post. The Associated Press report about the hospital battle in which Molhem was killed says the young photojournalist was following his brother, an FSA fighter.

Reuters was not alone in hiring such young stringers, Krupar says.

“I am sure there are much more young boys working in Syria in nowdays,” he writes. “Molhem was only one of them.”

Reuters global head of communications Barb Burg emailed to say that based on the agency’s communications with unspecified family members, Molhem was born in March 1995 and thus 18 years old when he began contributing to he agency and when he died. I’ve requested more details from Reuters and also from Syrian activists in Aleppo, who apparently first reported that he had been 17.

News organizations around the world have begun to pick up on this story, including the Guardian, France 24, the Huffington Post and several others. Petitions have begun to circulate as well.

A longtime Reuters bureau chief and Middle East regional editor who says he wrote the agency’s revised war-zone safety guidelines in 2008 — the same guidelines quoted below — has publicly criticized the company’s response. On Twitter

Andrew MacGregor Marshall, who resigned from Reuters in 2011 after 17 years with the agency, called his former employer’s initial response to questions about Molhem’s death shocking, sad and disgusting.

And on Facebook he writes further:

This is an extraordinary, cynically dishonest statement. As a veteran former Reuters journalist with extensive experience of working in dangerous and volatile war zones, I can say categorically that providing an explanation of why they deemed it appropriate to hire a teenager as a freelance photographer would not put any other journalists at risk.

I will post further updates over and after the holidays.

I’m glad to see interest in this case did not wane with the New Year.

Most recently David Kenner, the Middle East Editor at Foreign Policy magazine, has contributed some good reporting with a piece published last night on the magazine’s website.

Kenner’s story deserves to be read in full. However I will summarize some of the new information it contains here:

• The Aleppo Media Center, a pro-revolution propaganda organization, recruited Molhem in the winter of 2012.

• Within months, he was contributing photos to Reuters.

• Reuters confirmed that the agency supplied him with a camera.

• Reuters said for the first time that it also provided Molhem with a ballistic helmet and body armor.

• Molhem was supporting his parents with his income from Reuters.

• Molhem was secretive about and indeed may have lied about his age, knowing it could endanger his employment.

• Molhem’s true age remains in doubt.

Those who knew Barakat also cast doubt on Reuters’s claim [supported by unspecified family members] that he was 18 years old when the news agency began working with him. [Adnan Haddad, who recruited Barakat to the Aleppo Media Center] said that he is “sure” Barakat wasn’t 18. Journalists who knew Barakat in Aleppo said he was secretive about his age, knowing that it could place his employment in danger.

• Reuters may have published pictures taken by Molhem that were improperly credited to another photographer.

Wolfgang Bauer, a German journalist who covers Syria, met Barakat at a rebel-run media center in Aleppo’s Hanano neighborhood in September 2013. He said that Barakat was regularly sending pictures to Reuters at that point and had been filing photographs for some time under the name of an older photographer who served as a sort of “broker,” to avoid questions about his youth.

• Reuters “is continuing to look into the circumstances of his death.”

• “Barakat took the sort of risks that would horrify most veteran journalists.”

“The point is that, as with child soldiers, a guy his age will risk much more than an adult,” Bauer said. “If you’re 17 and need to feed your family by photography in a war area, that’s a very, very dangerous combination.”

As dramatic evidence of that last point, Kenner links to a YouTube video featuring Molhem playing an ambigous role amid combat.

The video was uploaded on Nov. 8 (which does not mean it was filmed on or near that date). It shows Molhem, clad in a sweater and bluejeans, tending to a wounded soldier.

This series of stills shows just how close Molhem was to danger.

Much contextual information is missing from the video. At a minimum, though, it illustrates the conditions that have caused Syria to be called the most dangerous place in the world today.

Once again Reuters has cited the presence of that danger to dismiss questions about this case. Echoing the agency’s earlier statement to the BBC, a Reuters spokesperson told Foreign Policy that it must be “cautious about discussing details of its relationship with [Molhem Barakat] ‘out of concern for the safety of other journalists in Syria.'”

This is disappointing, to say the least.

Now, on to the questions raised by Foreign Policy’s reporting.

- If Reuters provided safety equipment to Molhem, why was he not seen to be wearing it, not only in various photos and videos but also according to the recollections of photographers who knew him?

-

Was the safety equipment provided at the same time as the camera equipment, before or after? What was the relative timeframe of each provision?

-

Who provided the equipment? Did Reuters sanction and account for the provision or was it informal in nature?

-

Who was Molhem’s “broker” with the agency?

-

How did the broker pass payment on to Molhem? Was any money withheld?

-

How long did Molhem employ the broker (or vice-versa) before submitting to Reuters under his own name?

-

Was anyone else at Reuters aware of the “broker” arrangement? Who?

-

Was the broker also Molhem’s supervisor? If not, who was supervising Molhem and counseling him on acceptable versus unacceptable risks?

-

How will Reuters go about verifying the authenticity of other images submitted by the “broker” photographer?

-

Which family members told Reuters that Molhem was 18 years old?

-

Again: Has the family received any compensation or payment from Reuters? If not, has there been any discussion of this with the family?

-

Was the statement regarding Molhem’s age provided before or after any mention of compensation?

-

Who is conducting Reuters’ internal inquiry?

I do have one quibble with Kenner’s piece, and that is a dubious assertion made midway through, presumably in an effort to add balance.

Kenner writes that “news organizations cannot possibly afford to bring all these [freelancers] on as full-time staff members — a step that would bring with it pensions and long-term commitments that would make them hard to let go when the story died down.”

Granted, “afford” is a subjective term. But the statement leaves an impression that is misleading, as some numbers will demonstrate.

According to the running tally on Wikipedia, 153 journalists, the majority of them freelancers and “citizen journalists”, have been killed in the Syrian civil war since 2011.

Let’s say each one of those journalists would’ve cost an employer $150,000 a year in salary and benefits. (I’m certainly lowballing the costs of properly supporting a journalist in a war zone, however, this imaginary figure is also far more than most staff correspondents earn in a year.)

Now let’s imagine that Reuters — again, just for the sake of an example — decided to hire 153 journalists full-time at $150,000 a year to cover the conflict in Syria.

That would add up to $23 million — little more than a rounding error in the corporation’s $2 billion annual profit.

So it is demonstratably false that major media companies “cannot possibly afford” to hire full-time journalists.

The real issue is that fairly compensated war correspondents are source of red ink, not a source of profit, on the corporate balance sheet. The ownership and management of media companies were once more willing to absorb those losses in the interests of a public service mission or, more cynically, for the prestige value of “covering the world” and its difficult corners. Today, not so much.

The increasingly avaricious profit obsession in the media business comes at a time when traditional distinctions of combatant, civilian and correspondent have been vanishing. Consequently, freelance war reporters are assuming greater risk for diminishing rewards.

Who reaps the greater benefit from this arrangement? Who assumes the hardship?

Molhem’s case demonstrates like none other I’ve seen the widespread reluctance among journalists to confront some of the darkest practices of their industry, and an almost pathological refusal to hold news organizations to the same standards that journalists apply to government, big business and ordinary people who wind up in the news.

The concept of exploitation seems particularly elusive to some. Just because a person in a desperate position agrees to take outrageously excessive risks for outrageously miniscule pay does not mean that the arrangement is “OK.” The same flawed logic that says Molhem knew what he was getting into would excuse the deaths of all those factory workers in Bangladesh because, after all, they agreed to work in an unsafe factory.

Similarly, I’ve worked with photographers who had a death wish. It wasn’t my job to play Dr. Kevorkian for them!

Molhem’s willingness to work as a war correspondent did not dictate his fate. Older, more experienced players in the industry enabled his wish to work. In so doing, they assumed some responsibility for him.

His friend Hannah Lucci spoke of this burden in her earlier memorial:

He often asked me if he could work with me and I refused, because I didn’t want the responsibility of an eager seventeen year old with no war zone training and little experience on my shoulders. Soon afterwards I saw that he was filing photos for Reuters. I hope that they took responsibility for him in a way that I couldn’t, and I hope that if he was taking photographs as he died in the hope of selling them to that agency, they also take responsibility for him now.

Apart from the FP story, there was another important contribution to the discussion since my last update here.

On Dec. 30, Bang-Bang Club member Greg Marinovich published a soul-searching essay that addresses some of the larger moral, ethical and journalistic issues raised by Molhem’s death.

Marinovich brings invaluable expertise and credibility to the discussion and his essay also deserves a close reading.

“Why it is okay to risk the life of a ‘local’ in a desperately dangerous war-zone, when you are unwilling to send in someone that you are legally responsible for?” he writes.

Racism plays a role. Marinovich doesn’t say it, but I will.

He does bring up another matter that hasn’t been adequately grappled with —Â that is, the quality and reliability of Molhem’s work. The cheap labor status quo not only cheats freelancers, it cheats the reader.

If the photographs are good enough to go on the Reuters wire, or be moved by Getty, Corbis, AP, AFP, etc., then why are there differentials in pay? I have yet to see a disclaimer in the caption warning the readers that this is a cheaper (inferior?) image.

Marinovich ventures into tricky territory, praising Molhem’s obvious talent while raising legitimate questions about his discipline and experience.

Molhem was definitely a very good young photographer, some of his images are hauntingly beautiful; but others raise red flags. They looked either suicidally brave or were ‘managed’. I would be very curious to see what images did not make the wire.

Although I’ve been hesitant to discuss this here lest it distract from more important life-or-death issues, I agree with Marinovich’s gut check. Like many pictures from Syrian activists, a few of Molhem’s images had a staged feeling that is difficult to articulate and, at this point, all but impossible to verify one way or the other. This brings up a whole separate set of problems regarding the sourcing of images from Syria that I will address properly at some point.

Marinovich doesn’t dwell on this either, returning in his conclusion to the more urgent problem of working conditions, exploitation and corporate responsibility:

The media houses should to be more ethical, fairer, in how they treat local hires and freelancers, especially in war zones.

We talk of blood diamonds and have refused to wear running shoes stitched by exploited, underage labour; yet we are content to consume images made by teenagers who are paid peanuts.

Marinovich suggests we might collectively shun “blood photography.” I think the analogy is valid. What to do about it is another discussion, which will also have to wait.

To end this update, I have some new contextual information to add to my previous reporting here.

According to a source who scoured the Reuters wire for images attributed Molhem Barakat, the agency published 647 pictures by Molhem, with the first set dated August 15, 2013.

The source found no pictures prior to August and was uncertain why this was the case, since Reuters has stated Molhem’s contributions began last May. Once again I have asked Reuters for comment.

However, whether the source’s tally represents a portion or the full scope of Molhem’s published work for Reuters, it seems he deserved credit for more than the “dozens” of photos Reuters cited in its obituary.

The New York Times has come through with some answers on Reuters’ arrangement with Molhem.

The story, by Lens blog co-editor James Estrin and freelancer Karam Shoumali, was published on March 13.

It reveals that The Times interviewed Barakat’s father, Ahmad, a rebel commander, one week after Molhem’s death in Aleppo. It’s unclear why The Times did not publish a story based on the interview for some three months, or whether The Times conducted followup interviews as the story of Molhem’s death got more attention.

While the new story fills in some gaps, many crucial questions remain unanswered.

The best news it contains, from one company’s point of view, will be that Ahmad’s father thinks Reuters “did everything right.”

Reuters did provide Molhem with some safety gear, according to The Times, which concludes its story with this painful quote from Ahmad Barakat:

“The flak jacket and the helmet were buried with Molhem. They had his blood on them.â€

However, that seems to be where the company’s safety provisions for its young freelancer ended:

Reuters provided him with camera gear, a flak jacket and a helmet and paid him a day rate of $150. But four Syrian freelance photographers who worked for Reuters said that although they received protective jackets and helmets, they did not receive medical, safety or ethics training

Unfortunately The Times fails to address whether Reuters paid any form of compensation to Molhem’s family after the young man’s death. Reuters has simply ignored that question when I have put it to them directly.

Much of The Times story dwells, appropriately enough, on the journalistic problems revealed by Molhem’s case. Those problems are many and profound.

We learn:

-

[M]any of the [Reuters] freelancers are activists — in one case a spokesman — who supported the rebels. Three of them also said that the freelancers had provided Reuters with images that were staged or improperly credited, sometimes under pseudonyms. And while Reuters has given the local stringers protective vests and helmets, most said that the stringers lacked training in personal safety and first aid.

-

[S]ome of the Reuters freelancers staged photographs…

-

[Others used pseudonyms, which] “Reuters knew about…from the beginning.â€

The response from Reuters is, as ever, lame:

-

And although “we scrutinize all images and captions†to ensure they are free from bias, Reuters does not “as a general practice†inform subscribers that activists took the photos.

-

[A Reuters spokesperson] added that staging pictures was a firing offense but declined to say if anyone had been fired, citing personnel confidentiality.

Reuters responded further to the industry blog PetaPixel:

Reuters has made it clear to The Times during their three months of reporting that their allegations were false, and we refuted in detail any specific examples of alleged wrongdoing that that they provided us.

Except for anonymous allegations backed by no specific examples, the story provides no evidence that Reuters photographers have staged photos in Syria or anywhere else. We looked into the matter carefully and found no such instances. Staging photos is a firing offense, and Reuters would take appropriate action if we became aware of any instances of staging.

That statement doesn’t exactly convey introspection, does it? Nor does it convey sympathy. Nor is it convincing. The Times clearly did some legwork. What has Reuters done? Dug in its heels.

At least one noted Reuters stringer has quit over the company’s conduct in this case. According to the Columbia Journalism Review, “Motor City Muckraker” Steve Neavling “ended his relationship with Reuters when a teenage photographer for the wire service was killed on assignment in Syria.”

It didn’t sit well with Neavling morally; “I just sent them an email and said, ‘I’m done.’â€

Overall I’m grateful that The Times published its report. I wish it had answered even more questions, but what it contains remains damning.

Although The Times story pulls some punches, it also singles out Reuters for practices that are not exclusive to that company, but increasingly widespread in the news business. If Reuters hadn’t been so obstinate in its response to questions and criticism, I would think that was unfair.

Frankly I would have loved to have done some similar reporting on my own. In January and February I received requests for more information, but I simply didn’t have the resources to carry out first-hand fact-gathering in Syria, and no one who asked that I follow up the questions raised in this blog post was prepared to cover the costs of that reporting.

Finally, here are Reuters’ published guidelines regarding “dangerous situations.”

I have added emphasis where appropriate.

Dangerous Situations

The safety of our journalists, whether staff or freelance, is paramount. No story or image is worth a life. All assignments to zones of conflict and other dangerous areas are voluntary and no journalist will be penalised in any way for declining a hazardous assignment.

Journalists on the ground have complete discretion not to enter any danger zone. While all reporting of conflict and other hazardous environments involves an element of risk, you must avoid obvious danger and not take unreasonable risks. Writers may be able to produce as good a story at a safe distance as from the front line. Camera operators and photographers need to be closer to the action but using their experience and training often can enhance their security through careful choice of position.

You may move into a dangerous environment only with the authorisation of your superior. Wherever possible the senior regional editor for your discipline should be consulted. Assignments will be limited to those with experience of such circumstances and those under their direct supervision. No journalists will be assigned to a danger zone unless they have completed a Hostile Environment training course.

Your bureau chief/cluster chief and the regional Managing Editor are responsible for your safety and may order you not to run risks that you may consider acceptable. You must advise your base of your movements and of any significant increase in the danger you are exposed to whenever you have the opportunity to do so. If you decide a situation has become too dangerous and you withdraw unilaterally, that decision will be respected.

Do not move alone in a danger zone. If you travel by road do so as a passenger whenever possible, using a driver known and trusted by you and your companions, who is familiar with the terrain and with potential trouble spots. Your vehicle should be identified as a press car unless that would increase the risk. When possible, at least two cars should travel together at a reasonable distance apart in case of a breakdown. Do not travel in military or military-style vehicles unless you are with a regular military unit.

While correspondents, photographers and camera operators should work closely together in trouble zones, the differing nature of their work imposes different degrees of risk on them, and they may be safer working separately. Weigh the risks involved in each situation.

You, or someone in your party, must have a good knowledge of the local language or languages. If you do not speak the language, be sure to learn some key phrases such as foreign press, journalist, friend, various nationalities etc. Learn the local meaning of flags, signs, sound signals and gestures that could be important. Seek the advice of local authorities and residents about possible dangers.

Do not accompany or operate close to people carrying weapons without the explicit authorisation of your bureau chief or regional managing editor. Never carry a weapon or travel with journalists who do. Do not carry maps with markings that could be misconstrued. Be prudent in what you photograph or film. Seek the agreement of troops in the area before you take pictures. Always be conscious of the fact that troops may mistake camera equipment for weapons. Make every effort to demonstrate to them that you are not a threat. If you are unable to get agreement from troops before taking pictures, you must get authorisation from your bureau chief before proceeding, and must discuss with the bureau chief the safest way to get the pictures required. Carry identification, including a Reuters card, appropriate to the area where you are, unless being identified as a Reuters journalist would jeopardise your safety. If challenged, offer as much information about yourself as you can without compromising your safety. Never cross the line, or give the appearance of crossing the line, between the role of journalist as impartial observer and that of participant in a conflict. If working on both sides of a front line never give information to one side about military operations on the other side.

If caught in a situation where people are acting in a threatening manner, cocking their weapons and so on, try to stay relaxed and act friendly. Aggressive or nervous behaviour on your part is likely to be counter-productive. Carry cigarettes or other small luxuries you can use as an icebreaker.

Always wear civilian clothes unless accredited as a war correspondent and required to wear special dress. Use your judgment as to whether to dress to blend with the crowd or to be distinctively visible. In either case, avoid wearing military or paramilitary clothing. You should wear protective clothing such as a helmet and body armour in war zones as long as this does not increase the risks. You should also carry a gas mask and appropriate protective clothing if entering an area where there is a possibility that biological or chemical weapons may be used.

It is worth carrying the internationally recognised bracelet available with the caduceus symbol on one side and with space on the other on which to list your blood group and any allergies. The party you are travelling with should have a basic first-aid kit and a supply of sterile syringes.

Covering conflict and other stories of human suffering can be traumatic. Such reactions are normal and assistance is available through the Editorial Assistance Program or your local HR manager. Do not hesitate to seek this assistance if you think you would benefit. It will remain confidential.